These and other business owners, about 30 gay men and women, knew that because their interests were aligned, they would be stronger together. They formed the Desert Business Association, which is still around today. The unassuming name was purposely created to protect its members from homophobic reprisals by cloaking their common bond.

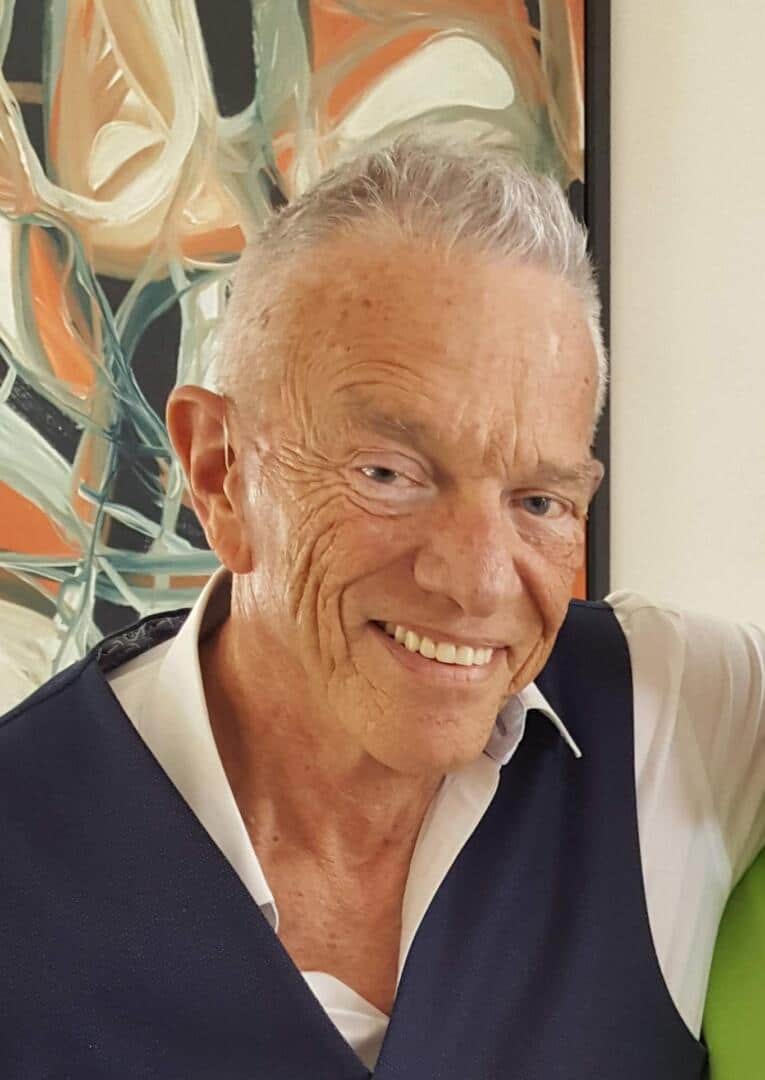

George Sonsel was already well established in Palm Springs as a director of social work and other related roles at area hospitals and with the County of Riverside. He had made his favorite vacation destination his home and was starting a private psychology practice on the side. But then then his friends and clients started dying horrible, sudden deaths, and doctors were baffled as to why.

That first year alone, Sonsel and his former partner lost 30-to-35 friends.

“Our friends kept dying in front of our eyes,” said Sonsel. “We no more than acknowledged their passing than we began to prepare for the death of another.”

This went on for about three years until Sonsel and his associates, made up of infectious disease doctors, oncologists, and the director of nurses at Desert Hospital (now called Desert Care Network) started accepting that this would not be a short epidemic.

For those who had access to government records, there was enough public health data now to make informed assumptions about the seriousness of the epidemic. This was before the Internet, and information traveled a lot slower if there was no community to spread the message or demand a dialogue.

Considering President Reagan would wait until the spring of 1987 to utter the word AIDS publicly, and never provided supportive leadership, American media and society itself was given free reign to ignore the suffering of AIDS patients and their loved ones. And as White House communications director Pat Buchanan called AIDS “nature’s revenge on gay men,” outright hostility towards those suffering was normalized.

The panic caused in many hospitals by lack of information and the seemingly random nature of the infection perpetuated stigma by numerous medical staff across the country. Many who were suffering from AIDS avoided going to the hospital out of fear of how they would be treated.

One of those motel owners called Sonsel and his partner one day, asking if they could come quickly.

“He’s dying,” their friend said. A male couple who was staying at the motel had come to Palm Springs so that one of them could die. They were too afraid to go to the local hospital after reading about how it was mistreating AIDS patients.

Despite urgings to accept care, they would not relent. Because of Sonsel’s state credentials, he was able to declare the dying man a threat to himself or others (aka 51/50) and had him forcibly transported to that very hospital, where the man died shortly after. The man’s partner left and went back to whatever part of the U.S. they came from.

This became commonplace for George Sonsel, his partner, and their network of friends and colleagues. These are the people we now call community activists, humanitarians, and heroes. Sonsel has a much more sobering viewpoint.

“We were taking care of our friends and so it didn’t feel like we were doing anything tremendous,” he said. “We were just doing what we felt we needed to do what we should do.”

Those early years (1979-1984) were largely without any information for those like Sonsel who were working to save their communities as health care workers and advocates. Today’s roadmap for community health that was created during the first years of the AIDS crisis was carved out by people who were too busy helping others to focus on their own broken hearts, even as the pangs of survivor’s guilt would taunt them.

“At times, I imagined my experience to feel like standing in the midst of a forest fire, somehow not personally consumed in flames, trying to extinguish an overwhelming inferno while watching in fear, desperation, and all-consuming guilt over your comrades being consumed or, at best, severely scarred for life by the flames,” said Sonsel.

There was no social safety net in place to absorb the cost of caring for those suffering with AIDS, and many of the early founders spent so much time caring for the sick and dying that they had to leave the careers that were supporting them. Also, it was common for doctors and nurses to avoid administering care out of fear of catching the mystery illness and giving it to their families.

The idea to establish non-profit status came from the desire to continue the vital work to care for the sick, but it took years. According to Sonsel, they had no hope of paying an attorney to assist them, but by doggedly pursuing and pleading with the Secretary of State’s office, eventually, they succeeded in 1984. It was around that time that he accepted a position at AIDS Project Los Angeles.

The co-founding of amfAR in 1983 by Elizabeth Taylor, and the tragic loss of Rock Hudson two years later mark a turning point for many. Celebrities started talking about the need for compassion, research, and the fundraising that was required to pay for this mission. Thank goodness for them.

But our celebrity icons were not the first ones to roll up their sleeves to fight AIDS. In the late 70s, unsung heroes across our country were doing what the government and many in the medical community would not. And many times it cost them their ability to support themselves financially.

George Sonsel survived that forest fire he described and is living contentedly with his husband Sven in the EU.

“Today my heart and soul feel at ease and that initial sense of urgency and desperation has been calmed,” he said. “That foundation we worked so hard to construct held and persevered.”

This article was originally published in the program for D.A.P.’s Steve Chase Humanitarian Awards, and is republished here with permission. In full disclosure, Desert AIDS Project is a sponsor of programming on PromoHomo.TV, but this series of six episodes on the occasion of D.A.P.’s 36th Anniversary is journalism, as Nicholas Snow Productions LLC does not offer “advertorial” (advertising disguised as reporting) content.